Palo Alto–Based Global Heritage Fund Takes a Modern Approach to Preserving the Past

Executive Director Nada Hosking seeks to bridge community and culture.

-

CategoryGiving Back, Homes + Spaces, Makers + Entrepreneurs, Sustainability

-

AboveGHFs Nada Hosking (left) and Dr. Salima Naji in Morocco. Naji, a Moroccan architect and anthropologist, is a GHF project director focused on the community protection of Amtoudi Sacred Communal Granaries in the Anti-Atlas Mountains. Naji was one of four female GHF Project Directors to speak at the groundbreaking GHF Women Leaders in World Heritage event at St. James’s Palace in London last September. — Photo by Steven Johnson, SeeBoundless LLC / Global Heritage Fund

There’s no endangered species list when it comes to human cultures. But in 2002, it was clear to Bay Area native Jeff Morgan that vital lifelines to our past were at risk of being permanently severed.

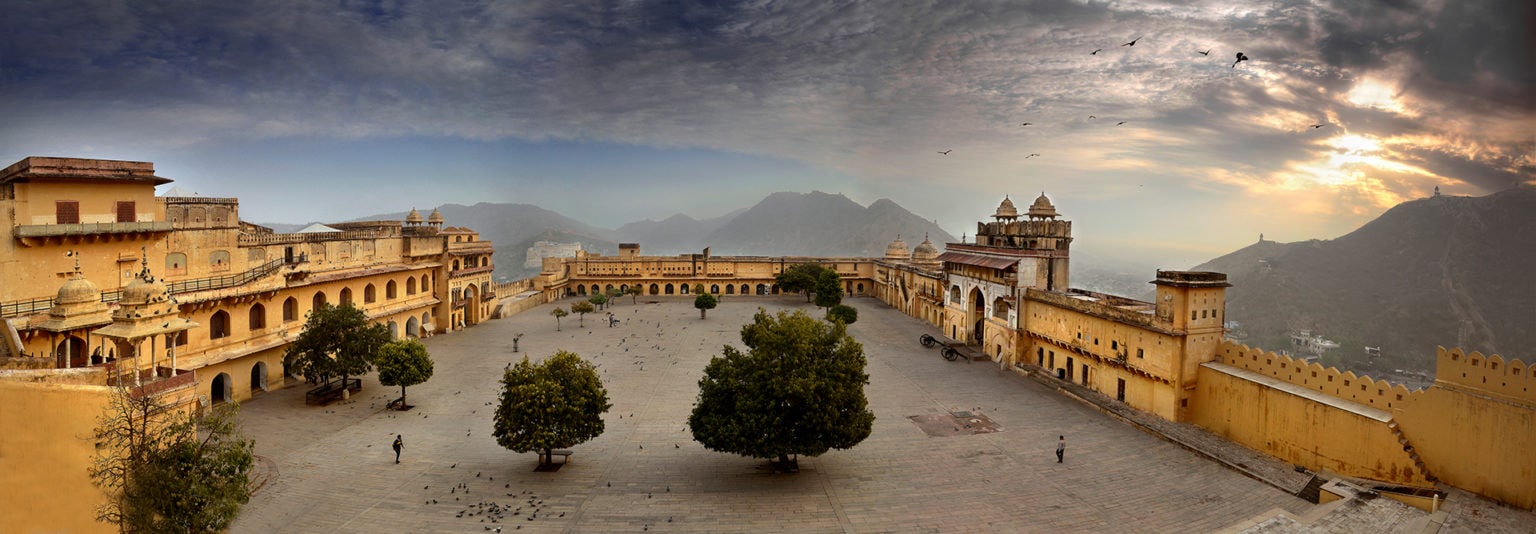

Above: The exquisite interior of the GHF project at India’s Amer Fort is adorned with intricate stone windows, delicately carved by hand with geometric patterns. The effect is stunning during the noonday sun.

— Photo by Amit Pasricha/Global Heritage Fund

That year, Morgan, a trained urban and regional planner with a Stanford MBA, founded the Palo Alto-based Global Heritage Fund (GHF), a nonprofit that works internationally to preserve cultural heritage sites in the developing world.

The organization stemmed from the belief that “cultural heritage is not anchored to the past but is a living companion of the present,” according to current GHF Chairman Daniel Thorne. Heritage, Thorne wrote in a report last year celebrating the group’s 15th anniversary, “can start—and continue in perpetuity—a virtuous cycle of sustainable economic growth and cultural renewal for its people…[and] can become a source of pride and of connection, the bond between the living, the dead, and those yet to be.”

Dali Village is located in Guizhou, a culturally rich but economically poor province in China’s mountainous west. With no industry and few tourists, Dali is experiencing a problem common to many ethnic villages in China’s hinterlands: to support their families, Dali’s residents must leave the village to find work, but by leaving, they slowly weaken the cultural bedrock that brings them home. To create new economic opportunities in Dali that would allow residents to stay and work full time, GHF has partnered with Studio Atlas to found a textile co-op for Dali’s women. Here two local girls wear traditional dress in Dali.

— Photo by Zhang Li/Global Heritage Fund

From its initial preservation project in Lijiang, China, to ongoing work in Greece, Colombia, Nepal, and other far-flung locations, GHF’s efforts have spanned 19 countries, 28 sites, and 114 partnerships with other government agencies and NGOs. The nonprofit also hosts trips to some of its project locations, so that members of the public can—as the GHF tagline states—“experience heritage through historic preservation beyond monuments.”

“The heritage sector is changing rapidly, and the tourism industry is evolving along with it,” explains GHF Executive Director Nada Hosking. “There is potential to wed heritage and tourism to create opportunities for travelers to interact with history in a fresh, people-centered way.”

Above: Amer Fort in Rajasthan, India, is a palace of lavish courtyards, ornate royal residences, and lush gardens. Intricate glass and metalwork are interspersed among towering walls of sandstone and marble, enticing visitors to wander through immense hallways and thick fortress walls. Once home to local rulers, Amer Fort’s opulent style and pioneering, eclectic mix of architectural motifs earned it a spot on the UNESCO World Heritage Site list in 2013. With history spanning hundreds of years, it is no surprise that Amer Fort’s management needs are complex and require careful balancing of stakeholder considerations. The Fort attracts a wide array of visitors, with over 1.8 million annual tourists and over 215,000 monthly tourists during its busiest periods. In response to these pressing visitor numbers, Global Heritage Fund recently supported the development of a management plan for this popular historic site.

— Photo by Amit Pasricha/Global Heritage Fund

“Major challenges exist in creating incentives that benefit local communities without encouraging the sort of over-development that is ruining popular places like Venice,” she acknowledges. “At GHF, we want to thread that needle between preservation and development.”

Hosking, who grew up in Morocco, has spent her career pursuing work that has international social impact. With a degree from UC Berkeley in History of Art and Anthropology, focusing specifically on archaeology, she went on to lead the Middle East and North Africa team for Global Fund for Women before joining GHF as Director of Programs and Partnerships. She took on her current role earlier this year.

Though she praises GHF for having “punched above its weight and made real inroads for cultural heritage,” Hosking admits this is challenging work. “While heritage sites may be universally loved, obtaining funding for community-based projects can be an uphill battle,” she shares. “Not everyone understands what it means to preserve cultural heritage through community empowerment—it’s a bit more complicated than raising funds to save a monument. There’s still a lot of work we need to do as a sector to inform the public about why local communities are critical to preservation success and sustainability.”

Global Heritage Fund (GHF) Executive Director Nada Hosking on a project in Morocco.

— Photo by Steven Johnson, SeeBoundless LLC / Global Heritage Fund

The work GHF has done so far sends a powerful message. The city of El Mirador, Guatemala was a Mayan settlement three times the size of Los Angeles that was once home to more than 200,000 people. Isolated and covered by a dense canopy of trees, the city’s ancient structures came under threat from agricultural development, logging, drug trafficking, and looting.

Over a 10-year period from 2005 – 2015, GHF and its partner agencies invested time and resources into sustainable tourism, job training, income generation, and more conservation-oriented agricultural practices. Notably, the groups organized a team of 40 specialists to survey, map, and assess the ecological and archaeological condition of the Mirador Basin—and in the process mapped 26 Mayan cities previously unknown to the Guatemalan government and discovered new architectural relics in El Mirador itself. All of those areas now have formal protection under the country’s constitution.

The Amtoudi Sacred Communal Granaries in the Anti-Atlas Mountains.

— Photo by Steven Johnson, SeeBoundless

There is a compelling human side to GHF’s work as well. Guatemalan citizen Juan Carlos Calderon grew up in a tiny community bordering Mirador Rio Azul National Park. Uneducated, unemployed, and desperate to feed and shelter his family, the adult Calderon turned to wildlife poaching and looting the Mayan artifacts he found in the ruins near his home.

Six years after GHF began its work in and around El Mirador, Calderon’s life had taken an unexpected turn; he took a job as a guard in the park where he was once a wanted man.

Continuing to focus on community-led projects is one of Hosking’s main goals in the coming years. “I believe that a people-centered approach to conservation of historic sites is the way forward because the built environment is a motivator for development,” she says. “Addressing the communities connected to historic sites ensures that people remain at the core of heritage management practice, which is a key component of sustainable preservation.”

GHF’s Nada Hosking.

— Photo by Steven Johnson, SeeBoundless

Over the years, GHF has opened regional headquarters in both Hong Kong and London, but its main base of operations remains in the Bay Area, affording the conservancy access to the technology and donor support that will be vital to GHF’s continued success, Hosking says. Hosking’s own alma mater, UC Berkeley, is responsible for important advances in digital technologies that aim to make archaeological sites more widely accessible and limit the destructive potential of excavations. “The Bay Area has an experimental nature and a high tolerance for trying out new ideas – that makes it a great place for innovative philanthropy,” she notes.

In his introduction to GHF’s 15th anniversary report, Daniel Thorne described cultural heritage as “a precious, non-renewable resource.” It’s a moving sentiment, and certainly true.

But cultural preservation is also just good economic practice, as noted by Silicon Valley VC legend William Draper III, who along with his wife Phyllis holds the title of GHF Global Heritage Ambassador. “Just as a venture capitalist evaluates potential investments, GHF has a unique lens through which it selects its sites,” Draper asserts. “GHF has discovered something that the international development world should take note of: heritage sites can be economic engines for countries that desperately need sustainable industries.”

Can California Become the “Champagne” of Cannabis?

It all comes down to intellectual property.

This Kern County Outlier Looks to Broaden Its Horizons with New Strains of Cannabis Industry

Can California City become a pot oasis in a dying desert?

Get the Latest Stories